This post covers the beginnings of the development of my most recent project, LEVIATHAN, an underwater monster hunting game. Here are the specific things I’ll be covering in this post:

- Intro: Leviathan is Born

- Part 1: Fish Behaviors

- Part 2: Player Movement

- Part 3: Boss Enemy Navigation

- Part 4: Music and Wwise Woes

- Part 5: itch.io’s Butler

- Part 6: Friends and Enemies

Intro: Leviathan is Born

After mulling over a few ideas and looking at some of my previous WIP projects, in December of 2022, I decided on what kind of game I would be making next and why. I decided on a 2D underwater side-scrolling shooter with a focus on fighting huge cybernetic sea monsters. Thematically, it would combine a number of my favorite things, namely huge monsters and the wonders and mysteries of the deep sea. As for the mechanics, the side-scrolling shooter with boss fights would allow me to work on a few key items:

- Proficiency with a commonly used prebuilt engine. With more and more developers shifting from in-house proprietary tech to prebuilt engines like Unity and Unreal, I wanted to attain proficiency with one of them. Since I had more prior knowledge and experience with Unity (and not intending to make anything approaching a 3D AAA game), I decided to go with Unity over Unreal.

- Game AI with complex, interesting behaviors. I focused on game AI during my master’s but hadn’t really done much with it since then.

- Action-oriented gameplay that rewards both quick thinking and mastery. Monster Hunter Rise had recently captured my attention, and I was hoping to emulate some of its better aspects.

- Implementation of animations. This was something I felt frustrated by in my previous experiences with Unity and wanted to devote time to figuring it out.

- Learning how to use audio middleware in Unity. While not strictly necessary, as an audio junkie I wanted to learn some of the ins and outs of Wwise and how it interacts with Unity.

With these goals in mind to drive me forward, I began work on what I would later title LEVIATHAN while visiting with family in sunny California. Although it was starting to show its age, my Microsoft Surface Pro 3 was perfectly adequate for starting a 2D project in Unity 2021.

Part 1: Fish Behaviors

With relatively little else on my mind, initial development for the project went smoothly. As it turns out, when a lot of your time has been spent working on lower-level programming, using something like Unity feels extraordinarily easy, at least initially. Within a couple days, I had some basic player movement and fish flocking behaviors up and running:

Having not implemented flocking before, I wasn’t sure how long it would take me, but thankfully it was a relatively painless process. Knowing that I would need more robust systems for handling boss AI later on, at this point I started investigating various implementations for behavior trees.

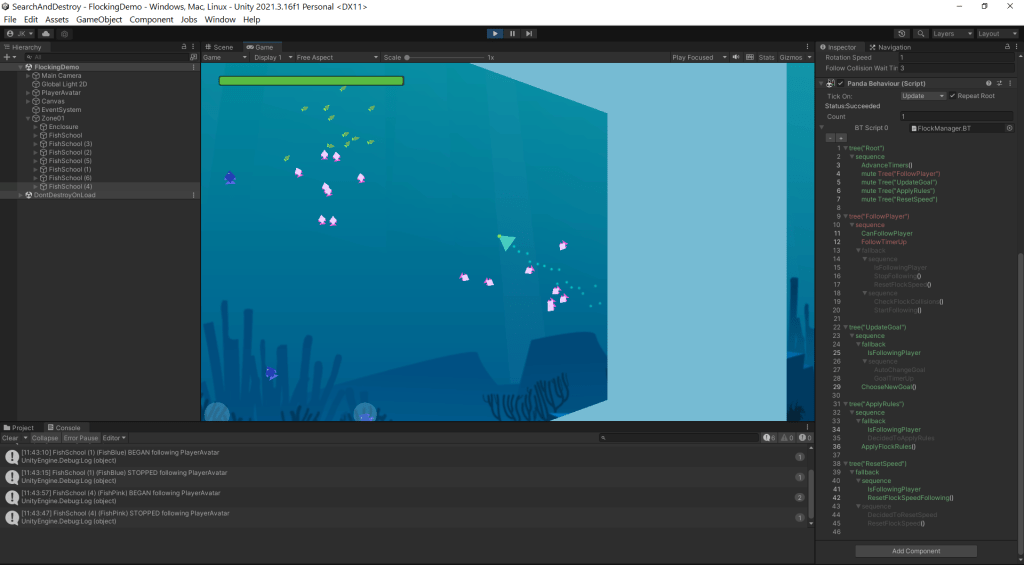

For whatever reason Unity doesn’t have anything built-in to handle this, but there were plenty of options on the Unity Asset Store. Not wanting to invest any money on the project just yet (and knowing I’d only be working a part-time job for the rest of the year), I ended up settling on Panda Behaviour, which eschews the more visual tree construction/debugging interfaces of more expensive options in favor of a lightweight scripting language. Importantly, despite the less visually friendly tree building process, you can see what parts of your behaviors are being executed at runtime, which was enough for me.

Here’s an example of the fish flock behavior, previously done purely in a Unity C# script, implemented as a Panda behavior tree:

In the inspector on the right, you can see the behavior running. Green text indicates nodes that have succeeded, while red text indicates nodes that have failed. There isn’t really a good way to tell at a glance which parts are execution nodes and which parts are flow control nodes (apart from some keywords like “sequence” and “fallback”), but in my experience so far this hasn’t been an issue.

Writing tasks / execution nodes in C# is straightforward enough; we just mark our function as a [Task] and then write in ThisTask.Succeed() to indicate when the task has completed. You can also fail tasks in a similar way if necessary.

[Task]

public void ResetFlockSpeed()

{

for (int i = 0; i < numObjectsInFlock; ++i)

ResetObjectSpeed(i);

ShouldResetSpeed = false;

ThisTask.Succeed();

}

Note that bool properties can be used as tasks as well, which is useful for flow control.

Part 2: Player Movement

Having completed fish behavior, arguably the most important aspect of any underwater game (the urge to ditch the game aspect and just make an aquarium screensaver is very real), I then moved on to player movement. One of the key aspects of Monster Hunter gameplay I wanted to retain was resource management, and movement is very much tied up in that.

I quickly implemented a “dash” mechanic and a regenerating stamina resource, along with some simple UI to visualize it. I also created a system (not shown here) whereby players can gain boosts to their stamina and speed after swimming through enough fish. While not everything I’m doing with movement is realistic for a submarine (or whatever the player avatar ends up being), I’m reasonably sure most people will accept that it needs to work the way it does for the game to be fun and interesting.

Hunting monsters with friends is always more fun, so from the beginning I had planned for two-player local co-op. One day, when I wanted a break from on gameplay features, I mocked up a title screen reminiscent of something you might see on an arcade machine:

Implementing actual co-op features ended up being more of a pain than I anticipated, but thanks to Unity’s new input system and Cinemachine, I was able to avoid writing too many systems from scratch. I’ll probably end up devoting a post or part of a post to those aspects later once development is a little further along.

Part 3: Boss Enemy Navigation

After fiddling around with player controls and movement for a while, it was time to bite the bullet and start dealing with boss AI. Rather than having bosses that are confined to specific areas of a map, I wanted more dynamic boss fights that could occur in any number of different locations. Since I hadn’t used Unity’s nav mesh system before, I decided to tackle that first.

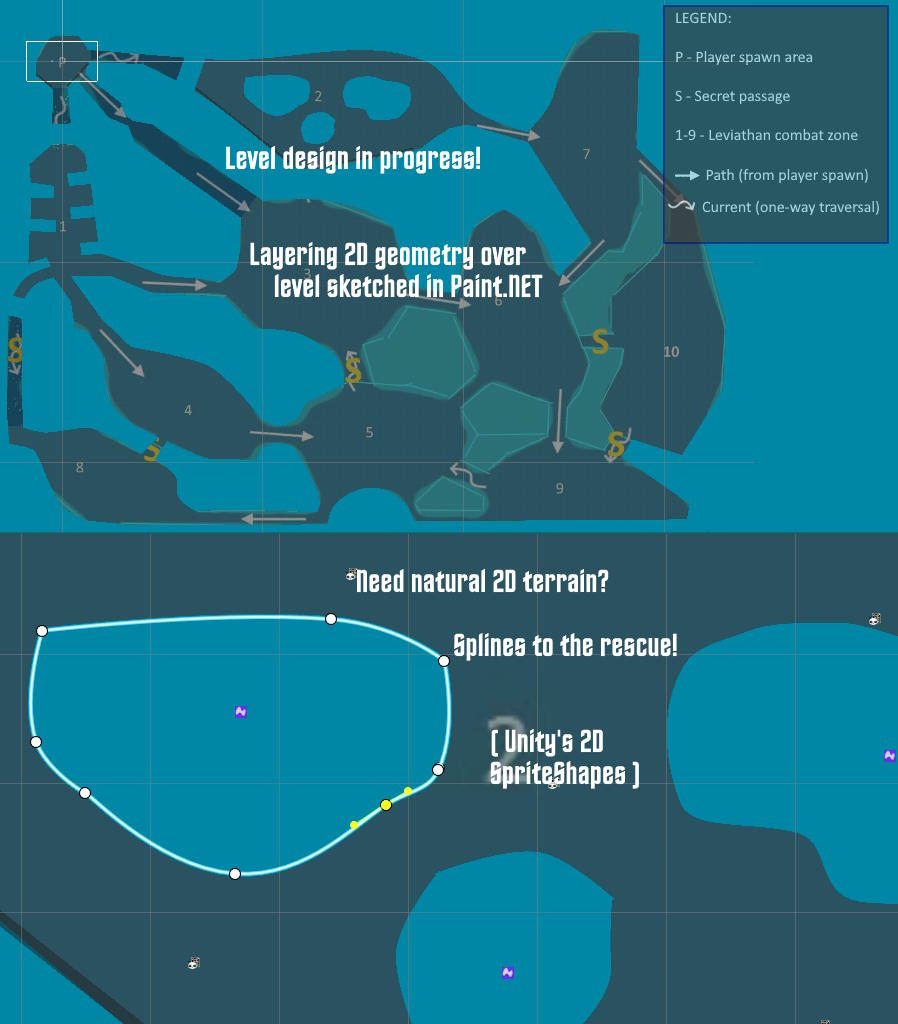

After mocking up a level in Paint.NET, I used Unity’s 2D SpriteShape tool to create the geometry for the level in the editor. Getting nav meshes to work properly for a 2D game required jumping through some hoops, even with the aid of the custom NavMeshPlus package. I would be more specific, but the series of steps I had to take was not at all intuitive, so I don’t remember exactly what they were. Point is, it works now, which is the important thing.

To better allow me to track the location of the player and (for testing purposes) the boss enemies, I created a minimap, which you can see in the GIF above. In this GIF, the boss enemy (E) uses a secret passage to traverse from its original location near the top of the map to a zone at the bottom. A water current quickly propels the player avatar (P1) from the starting zone to one of the adjacent zones.

While I knew bosses would require a lot of work over the lifetime of the project, being able to at least cross off zone-to-zone navigation for bosses felt great.

Part 4: Music and Wwise Woes

As stated in the introduction, one of my goals for this project was to learn about Wwise and how it integrates with engines like Unity and Unreal. I had prior experience with audio middleware in custom engines (FMOD, specifically), but had little to no experience trying to integrate them with complex engines/toolsets like Unity.

Why use audio middleware at all? Unity already has a built-in audio system, so what’s the benefit? Well, from an implementation perspective, Unity’s audio system isn’t built to have more than one active listener in a scene, which is kind of important for a game with local split-screen co-op. Wwise and FMOD can do this out of the box, which is a big plus. The main thing, though, is it gives sound designers a way to author logic relating to the sound design of the game without having to touch the engine itself. If I got someone else to work on sounds, this would be a huge benefit, not to mention I was already curious about the Wwise workflow and integration.

Now that we have the benefits out of the way, here are some things I really wish I’d known before I’d committed to using Wwise with my project:

- Wwise doesn’t currently support web deployment (as of the time of this writing), which means a Unity project that uses Wwise can’t be built for WebGL

- Targeting multiple platforms can dramatically increase the size of your Wwise project

- Even for someone who’s moderately familiar with how game audio works, the Wwise authoring tool is not intuitive

While I don’t know that any of these would have necessarily changed my decision, solo developers are probably better off avoiding the added complexity that this kind of professional-grade middleware introduces. Now that I’ve had some time to work with it, I’m looking forward to seeing what cool stuff can be done with Wwise.

At the moment, I only have music – tracks written by yours truly – implemented; the background music transitions between a number of different tracks based on whether a player is fighting a boss, chasing a boss, or exploring. Until I have time to write dedicated music for the game, I’m using this pre-existing track as a basis for the combat and exploration music:

And this is the current main menu track, which I think I like well enough to keep for the long-haul:

Part 5: itch.io’s Butler

Once we have a version that will be useful for playtesting, itch.io will likely end up being our distribution platform. With that in mind, I created a private page for the game on itch and uploaded a build for internal testing. Unity projects, once built, can get a bit large and, while at this stage there weren’t that many assets in the game, it was easy to see that trying to upload a “quick fix” would take a bit longer than I was willing to wait if I had to upload the entire build every time.

Thankfully, itch has a solution for this in the form of butler, a command-line tool that lets you push and manage multiple kinds of builds to your itch pages. The biggest selling point for me is that it only uploads what’s different between subsequent builds, meaning what might normally be and upload of hundreds of megabytes ends up being a fraction of that in most cases.

If you’re using itch for your game pages and your games are anywhere close in size to what Unity and Unreal projects can be, you owe it to yourself to check out butler!

Part 6: Friends and Enemies

Having dealt with all kinds of issues not actually related to gameplay, I was glad to finally get back to implementing game features. Using a combination of free and relatively cheap paid assets, I worked on improving the look of the environment. I then hacked together some slightly better UI for the player’s stamina (now called “energy” to better reflect the player avatar being a mechanical object) and the newly added health and ammo resources.

I also did some work on smaller enemy behaviors in preparation for working on more complex boss enemies. You can see all of this along with a test of Unity’s nifty 2D lighting system in the video below.

I was having a great time on the project by this point, but I didn’t want to limit myself to simple geometric shapes for most of the art, in particular the boss enemies. I’ve also realized over the years that, while I can try to do everything myself, the result is better and I’m more motivated when working with others. I’m no artist, that’s for certain! With that in mind, I sought out assistance from my coworkers for art and sound effects.

Since my coworkers were still working full-time, progress on those fronts has been understandably slow, but with summer swiftly approaching, I recently had the opportunity to sit down and hash some things out with Michael, our artist. We’re now doing research on what style to use, how the pipeline will work with Unity, and figuring out what our enemies and bosses will be. We also clarified the scope of the project, ultimately deciding to focus on a vertical slice with one level and two bosses, along with a small assortment of non-hostile critters and lower-tier enemies.

Conclusion

While there are certainly things I’ve glossed over in this post, I’ve made an effort cover everything I’ve made screenshots and footage for so far in the project’s development. Now that the semester is nearly over (as well as my final year of teaching), my intent is to do shorter, more frequent posts as I work on the game. Granted, I’ll also be doing a fair amount of job-hunting, so we’ll see how well I live up to that promise, but regardless I expect work on the game to pick up a fair bit in the coming weeks.

Thanks for reading and stay tuned for more updates!

One thought on “Leviathan Dev Log #1: Rising from the Deep”